In the preface to the second edition of his book published in 1959, Islam in India and Pakistan, Murray T. Titus, a US academic and Christian missionary, gives thanks to several people who helped him write his book which was originally written as a PhD thesis undertaken at the Hartford Seminary Foundation in the 1920s. At the top of the list of people who Titus expresses his appreciation to is the then principal and head lecturer in hadith at Darul Uloom Deoband and also renowned Indian freedom fighter, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Sayyid Husain Ahmad Madani (1879-1957). [1]According to Hobson Jobson (the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words and terms from Indian languages), the word khutput “is a native slang term in Western India for a prevalent system of intrigue and corruption” and that the general meaning of khutpuṭ in Hindustani and Marathi is “wrangling” and “worry.” It is in this sense that this word has been used in this article.

In the preface to the second edition of his book published in 1959, Islam in India and Pakistan, Murray T. Titus, a US academic and Christian missionary, gives thanks to several people who helped him write his book which was originally written as a PhD thesis undertaken at the Hartford Seminary Foundation in the 1920s. At the top of the list of people who Titus expresses his appreciation to is the then principal and head lecturer in hadith at Darul Uloom Deoband and also renowned Indian freedom fighter, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Sayyid Husain Ahmad Madani (1879-1957). [1]According to Hobson Jobson (the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words and terms from Indian languages), the word khutput “is a native slang term in Western India for a prevalent system of intrigue and corruption” and that the general meaning of khutpuṭ in Hindustani and Marathi is “wrangling” and “worry.” It is in this sense that this word has been used in this article.

This note of thanks is not in anyway remarkable, and why should it be? Educational institutes and people of learning the world over often collaborate with each other, assisting in the sharing and dissemination of learning and knowledge. This is something that often happens and for the mother of all Deobandi institutes, the Darul Uloom Deoband, to be involved in such a collaboration is not any different. Titus’ note is not isolated after all there are numerous similar successful partnerships.

It does, therefore, come as a bit of a surprise when researchers on the study of Islam in the UK fail to access Darul Ulooms in the British Isles and then write miserable lamentations about closed worlds, make unsubstantiated claims that non-access is the default “Deobandi” position when it is the exception, and furnish “reasons” for their failure that seem anchored on conjecture rather than substance—a picture of sour grapes to say the least. One such example is that of Sophie Gilliat-Ray, Professor of Religious and Theological Studies and Founding Director of the Centre for the Study of Islam in the UK at Cardiff University. It was in 2005 that Gilliat-Ray wrote a paper on her inability to access Deobandi Darul Ulooms in the UK, entitled Closed Worlds, (Not) Accessing Deobandi dar ul-uloom in Britain. Some years later in 2018, Gilliat-Ray wrote another paper following up on this entitled From “Closed Worlds” to “Open Doors”: (Now) Accessing Deobandi Darul Uloom in Britain.

As the provocative title suggests, Gilliat-Ray’s first paper impresses on readers that non-access is the default position in Deobandi Darul Ulooms and that the “world of British dar ul-uloom remains shrouded in mystery to many, and this includes both Muslims and non-Muslims alike.” She carries on with this theme in the paper, writing, “However, in relation to British Deobandi dar ul-uloom, this isolationism is compounded by the political and historical circumstances in which their ‘parent’ institutions were formed.”

In her second paper, Gilliat-Ray continues with this theme of considering the Darul Ulooms to be isolationist and non-engaging. She also provides the background to why and how she attempted to access Deobandi Darul Ulooms in the UK for social research and furnishes four reasons why she felt access was denied (though she mentions she has recently been given partial access at an institute in the south of England). She also writes that her original paper gained some “notoriety” and negativity within Deobandi circles, criticism that she brushes aside by describing them as “rumours” and “gossip” than actual readings of her writings.

In this article, I hope to discuss Gilliat-Ray’s four reasons (though not in order) and also mention other considerations that may have influenced why she was denied access. It would also be necessary to mention that though I myself am a graduate of a UK-based Darul Uloom, I have never had any involvement in the running of Darul Ulooms nor am I privy to their views on why Gilliat-Ray was denied access. What I write in this paper, I write in my own personal capacity as an observer. However, prior to discussing Gilliat-Ray’s four reasons, I would like to set the scene by listing several media reports, two TV documentaries and one academic paper relating to the UK’s first Darul Uloom, the one at Bury. Though this is not an exhaustive list, it does demonstrate how the earliest Darul Uloom in the UK, from its inception in the late 1970s, has not only opened its doors to news reporters and academics, but also engaged civic society and British television.

Darul Uloom Bury engaging the media, civic society and academics

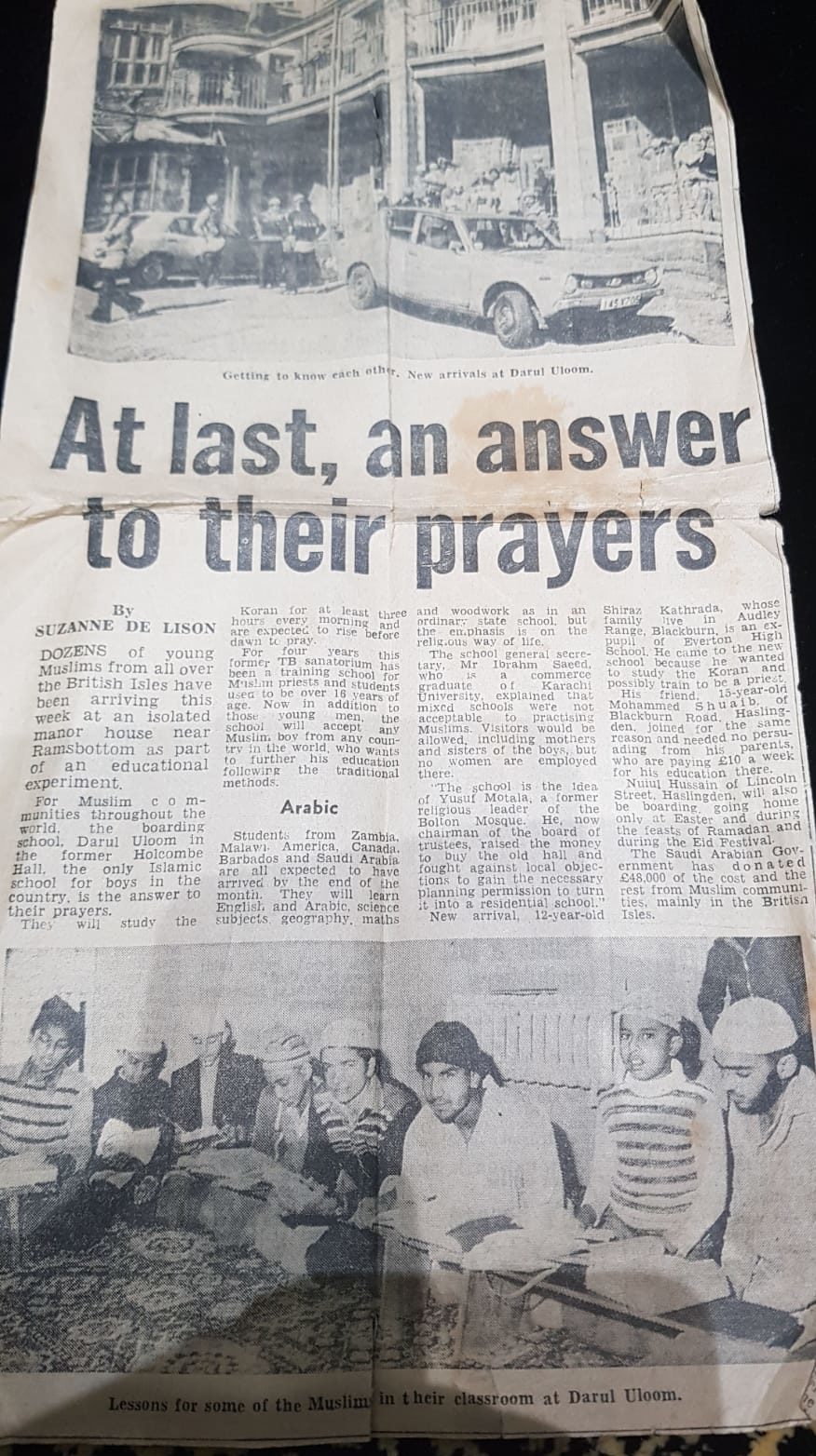

[1] The Lancashire Telegraph published an article on 25 September 1979 with the headline “At last, an answer to their prayers.” The report mentions:

“Dozens of young Muslims from all over the British Isles have been arriving this week at an isolated manor house near Ramsbottom as part of an educational experiment. For Muslim communities throughout the world, the boarding school, Darul Uloom in the former Holcombe Hall, the only Islamic school for boys in the country, is the answer to their prayers.”

The article includes comments from the Darul Uloom’s then General Secretary Ibrahim Saeed and students. It is also illustrated with photographs of students standing at the entrance of the building. Another noteworthy point is that the reporter is female (more on this later).

The article includes comments from the Darul Uloom’s then General Secretary Ibrahim Saeed and students. It is also illustrated with photographs of students standing at the entrance of the building. Another noteworthy point is that the reporter is female (more on this later).

[2] The principal of Darul Uloom Bury, the late Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Yusuf Motala (1946-2019) is acknowledged and thanked in the beginning pages of Islam in Preston, an academic study on the social and religious life of Muslims in Preston that seems to have been commissioned by the local authority for schoolteachers and published in 1980. Darul Uloom Bury and its educational offering are discussed in detail within the context of imam training in Britain in relation to mosques in Preston.

[3] Credo, a religious affairs programme produced by London Weekend Television for ITV and broadcast on Sunday evenings, ran a programme entitled Schools for Moslems in 1980. The documentary makers gained access to Darul Uloom Bury and filmed students during a normal day, in classrooms (both secular and Islamic), at meal times, praying and playing football. The crew also filmed the grounds and inside the building (including accommodation). They also interviewed students and staff. Incidentally, one of the members of staff filmed at the Darul Uloom was a non-Muslim female. Interestingly, the programme’s researcher, as can be understood from the credits at the end, was also female who must have contacted the Darul Uloom and most likely accompanied the crew during the visit.

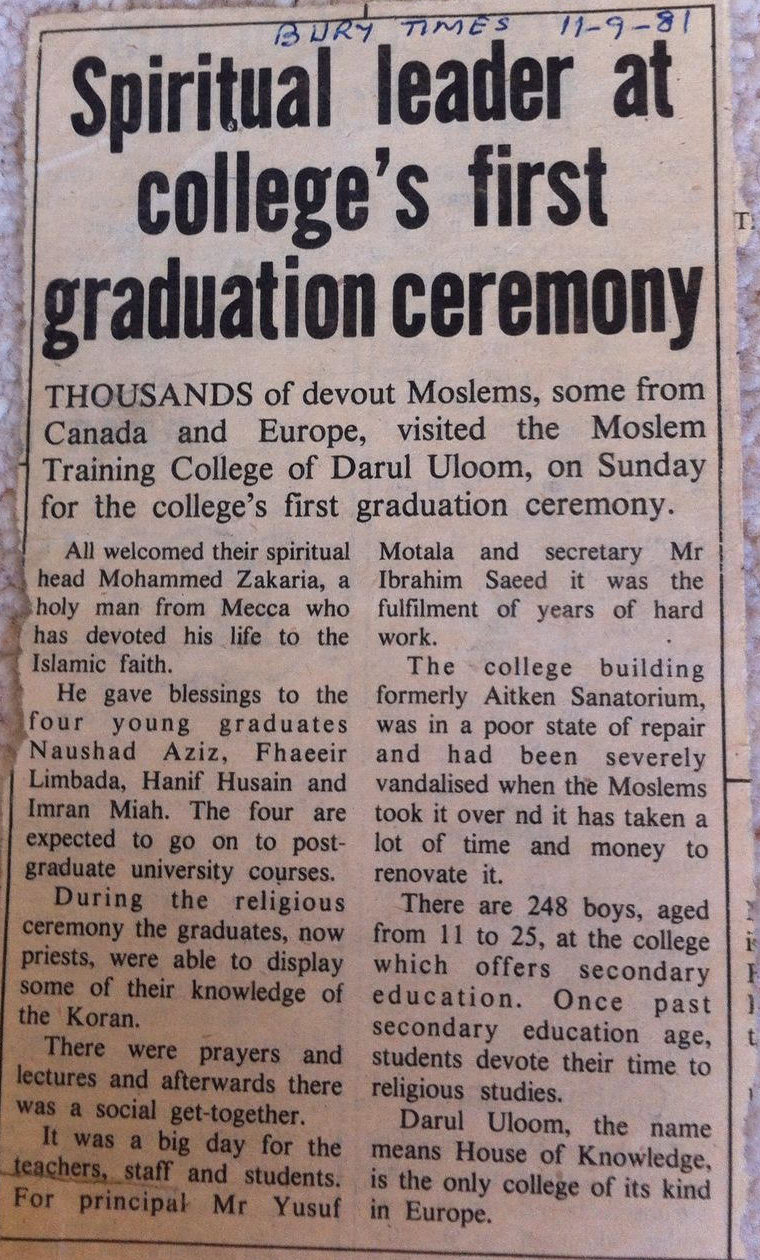

[4] The Bury Times published an article on 11 September 1981 with the  headline “Spiritual leader at college’s first graduation ceremony.” The lead paragraph was:

headline “Spiritual leader at college’s first graduation ceremony.” The lead paragraph was:

“Thousands of devout Moslems, some from Canada and Europe, visited the Moslem Training College of Darul Uloom, on Sunday for the college’s first graduation ceremony.”

The article discusses Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Muhammad Zakariyya Kandhalwi’s visit to Darul Uloom Bury in the following words, “All welcomed their spiritual head Mohammed Zakaria, a holy man from Mecca who has devoted his life to the Islamic faith.” It then names the four graduating students and adds that they “are expected to go on to post-graduate university courses.” The account, thereafter, is an insider’s view of what took place at the event with the report adding that “it was a big day for the teachers, staff and students. For principal Mr Yusuf Motala and secretary Mr Ibrahim Saeed it was the fulfilment of years of hard work.”

[5] Credo, the ITV religious affairs programme discussed above, again visited Darul Uloom Bury for another documentary entitled Muslim Schools in 1985. There is, unfortunately, no footage available of this online though photographs of the visit can be found on stock photography provider Shutterstock.com. Nevertheless, this is another example of how the UK’s earliest Darul Uloom engaged with British television.

[6] The Bury Times published an article on 20 September 2002 with the headline “College marks achievements.” This is a very short article that includes the following text:

“People from all walks of life came together to celebrate the achievements of Bury’s Islamic school. Invited guests were given a tour of Darul Uloom college in Holcombe, which has been providing education in a faith-based environment for 26 years.”

The story is illustrated with a photograph of a number of people that include staff and several visitors, including a local MP, a bishop, a senior police officer and a vicar. One of the visitors is also female.

Screen grab of an English lesson at Darul Uloom Bury from ITV’s religious affairs programme CREDO broadcast in 1980

[7] BBC Online published an article on 14 January 2004 with the headline Inside Britain’s Islamic Colleges. The article leads by saying, “what goes on in Islamic colleges – and why are they so worried about how they are portrayed?” The reporter gained access to two large UK Darul Ulooms, one in Bury and another in Blackburn. Interestingly, Gilliat-Ray attempted to access Darul Ulooms between January and September 2004 and subsequently published her first paper in 2005. As someone researching Darul Ulooms it is surprising that this BBC article received no mention in her paper, instead readers are told that the “world of British dar ul-uloom remains shrouded in mystery.”

[8] The Bury Times once more published an article on 20 July 2004 with the headline College opens its doors for a look behind the scenes. This article leads by saying “politicians, church leaders and schools gathered together to enjoy an insight into Darul Uloom College” which “held its annual open day to show visitors how the college is run and what life is like for the hundreds of students.”

Visitors included the MP for Bolton, a councillor who was representing the MP for Bury North, and representatives of local schools, churches and other groups. Students and ex-students also delivered speeches, including one who spoke on his experiences of moving from the Darul Uloom to university. The story was illustrated with a photograph of the late principal of Darul Uloom Bury, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Yusuf Motala with his grandchildren and the visitors who included several females. Again, this article was published just after Gilliat-Ray’s unsuccessful attempt to access Darul Ulooms and prior to the publishing of her first paper in 2005.

[9] The Muslim News ran an interview with the principal of Darul Uloom Bury on 28 January 2011 with the headline Shaykh

[9] The Muslim News ran an interview with the principal of Darul Uloom Bury on 28 January 2011 with the headline Shaykh

Yusuf Motala, promoting positive citizenship. The article mentions how the mawlana has always attempted political and diplomatic solutions to social challenges and legislative changes, and that he has constantly called for British Muslims to participate and engage in politics (specifically with the main political parties) to contribute to the civil and public spheres.

It adds that Darul Uloom Bury is nestled in the midst of a hundred thousand homes of which a mere twenty are Muslim and that the mawlana suggests this is as an example of meaningful engagement. “The residents do not merely tolerate the existence of the Darul Uloom but they have accepted it,” said the mawlana, adding that the “genuine engagement, generosity, warmth and the understanding of the staff, teachers and students” have contributed to this. The article also touches on community relations and steps the mawlana himself has previously taken to calm communities and avoid divisions. It further adds that he “opposes ignorance and aspires for Muslims to serve valuable roles in society… for the one who has good intentions to provide this service, he has ample opportunities available to him…”

Having set the scene, we now turn to Gilliat-Ray’s four reasons (though not in order).

Gilliat-Ray’s Fourth Consideration

Gilliat-Ray feels that one of the reasons why she was denied access to Darul Ulooms (which is the last one) was due to an “anathema of social scientific enquiry” and no “appreciation of social scientific knowledge” within them:

“The lack of access was perhaps related to a fourth consideration, namely, the anathema of social scientific enquiry within these institutions (Hornsby-Smith 1993). While valuing knowledge, it seemed that this did not extend to appreciation of social scientific knowledge, certainly in comparison to the mastery of divinely-revealed religious texts and classical commentaries. ‘What any group counts as ‘knowledge’ is … a social product’ (Spickard 2002: 247), and my work clearly ‘didn’t count.’”

Is it the case that there is an anathema for social scientific enquiry within Darul Ulooms? Though Gilliat-Ray has referenced her above claim, none of the references refer to academic studies on the supposed anathema of social scientific enquiry within actual Darul Ulooms. On the contrary, there are in fact numerous occasions when Darul Ulooms and those associated with them not only undertook social scientific enquiry themselves, but collaborated with academics, including those from the West, in the study of knowledge beyond just divinely-revealed religious texts and classic commentaries, such as social science, history, political science, etc.

As discussed above, the principal of Darul Uloom Bury, the late Mawlana Yusuf Motala, was acknowledged and thanked in the beginning pages of Islam in Preston. Clearly, if there was an anathema for social scientific enquiry within Darul Ulooms then the late Mawlana Yusuf Motala would not have taken liberty to engage with the authors of this academic study.

Anyone familiar with the writings of the late mawlana’s teacher and Sufi mentor, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Muhammad Zakariyya Kandhawi would know that the Shaykh al-Hadith himself employed tools used in social scientific enquiry to inform at least two of his writings: Akabir ka Ramadan (a description of the habits and practices of senior Indian scholars in Ramadan) and his lengthy and beautiful introduction to Ikmal al-Shiyam (an Urdu commentary on the aphorisms of the 13th century Sufi Ibn ‘Ataullah al-Iskandari). In gathering material for both of these empirical writings, the Shaykh al-Hadith circulated a questionnaire and used the responses he received to inform his writing.

Likewise, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Yusuf Motala expanded on this  methodology of social scientific enquiry in drafting his first major work, a biography of his shaykh entitled Hadhrat Shaykh awr unke Khulafa. The mawlana drafted a questionnaire that was circulated to the khalifahs of Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Muhammad Zakariyya Kandhawi who in turn participated in the “enquiry” and contributed in the creation of knowledge. The responses were used to compile the three-volume biography that includes two volumes on the lives of the majority of the shaykh’s spiritual Sufi successors (khalifahs). Aside from this, as part of students’ independent studies at Darul Uloom Bury, for some years the mawlana would request students to carry out biographical research and do a write up of their findings, something that qualifies as qualitative research.

methodology of social scientific enquiry in drafting his first major work, a biography of his shaykh entitled Hadhrat Shaykh awr unke Khulafa. The mawlana drafted a questionnaire that was circulated to the khalifahs of Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Muhammad Zakariyya Kandhawi who in turn participated in the “enquiry” and contributed in the creation of knowledge. The responses were used to compile the three-volume biography that includes two volumes on the lives of the majority of the shaykh’s spiritual Sufi successors (khalifahs). Aside from this, as part of students’ independent studies at Darul Uloom Bury, for some years the mawlana would request students to carry out biographical research and do a write up of their findings, something that qualifies as qualitative research.

Further, in the mid-1980s at the height of discussions around the visibility of the new moon in the UK and where Muslims in the UK should acquire news of the new lunar month as well as determining prayer times during twilight nights, Mawlana Yusuf would actively encourage senior students to undertake observations of the sky at night and moon phases from Holcombe Hill. These observances provided qualitative data and were followed by quantitative research and discussions to formulate a critically informed viewpoint. To suggest, or rather assert, that access was denied due to an “anathema of social enquiry” is preposterous to say the least and academic anathema too.

To exemplify this point further, here is a non-exhaustive list of a few occasions when the mother of all madrasahs within the Deobandi tradition, the Darul Uloom at Deoband in India, for example, collaborated with academic institutes on various subjects beyond what the madrasahs would refer to as the transmitted sciences (manqulat):

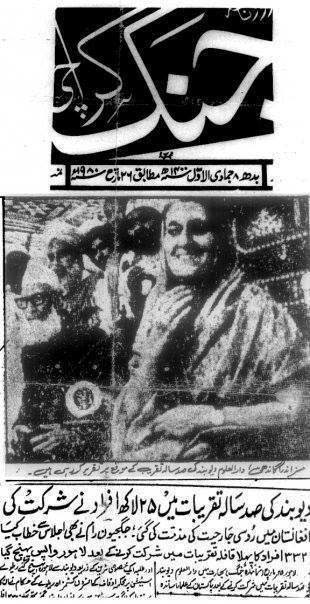

[1] In 1964 the Darul Uloom participated in the 26th International Congress of Orientalists, a forum for predominantly Orientalist scholars from Europe and the US. This session was held in New Delhi with 1,100 scholars attending, including 500 from abroad and 600 from India. The Darul Uloom used the opportunity to display its rare manuscripts at one of the conference’s exhibitions dedicated to this subject. Visiting scholars “looked at them particularly with approval and took notes from several of them.” (History of the Darul Uloom Deoband, Vol.1 – page 294)

[2] Dr Peter Hardy, Reader in the History of Islam in South Asia and a lecturer in the SOAS History Department from 1947 to 1983, visited Darul Uloom Deoband in circa 1969 (1380AH) for research and remained at the Darul Uloom for almost a week, where he met and held lengthy conversations with the then rector, Qari Muhammad Tayyib Qasmi (1897-1983). Pleased by his visit, he later wrote, “It was with the expectation of finding much valuable material on Islam in India that I wished to visit Darul Uloom Deoband. Not only was that expectation completely fulfilled but moreover I was overwhelmed with kindness, hospitality and invaluable guidance by the learned Ulama of the institution…” (History of the Darul Uloom Deoband, Vol.1 – page 277)

[2] Dr Peter Hardy, Reader in the History of Islam in South Asia and a lecturer in the SOAS History Department from 1947 to 1983, visited Darul Uloom Deoband in circa 1969 (1380AH) for research and remained at the Darul Uloom for almost a week, where he met and held lengthy conversations with the then rector, Qari Muhammad Tayyib Qasmi (1897-1983). Pleased by his visit, he later wrote, “It was with the expectation of finding much valuable material on Islam in India that I wished to visit Darul Uloom Deoband. Not only was that expectation completely fulfilled but moreover I was overwhelmed with kindness, hospitality and invaluable guidance by the learned Ulama of the institution…” (History of the Darul Uloom Deoband, Vol.1 – page 277)

[3] The Darul Uloom also hosted Gail Minault Graham, a female researcher from the University of Pennsylvania, who was carrying out research relating to a dissertation that she was writing: The Khilafat Movement: A Study of Indian Muslim Leadership (1972). This was subsequently published in book form entitled The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India. (History of the Darul Uloom Deoband, Vol.1 – page 303)

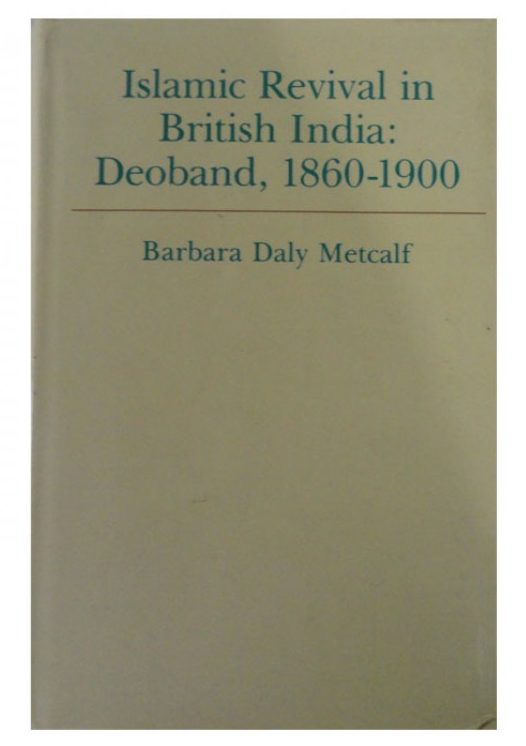

[4] Barbara Metcalf, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of California, visited Darul Uloom for her doctoral dissertation on the history of Muslim religious scholars of Deoband in the early 1970s. This was also subsequently published in book form under the title Islamic Revival in British India – Deoband, 1860-1900. During the course of her research, the then rector Qari Muhammad Tayyib Qasmi hosted Metcalf in Deoband and also at his home on several occasions. (History of the Darul Uloom Deoband, Vol.1 – page 303)

[5] The second volume of the History of the Darul Uloom Deoband includes a list of “respectable visitors” to the madrasah over the years, in which the names of several academics can be seen, including a professor from Oxford University. Interestingly, another visitor was Sir James Norman Dalrymple Anderson, an English lawyer, missionary and Arabist, who visited the madrasah in his capacity as Professor of Oriental Laws at the University of London, again for research.

[6] Reverend David Emmanuel Singh, a research tutor in Islamic studies at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, thanks a number of Darul Ulooms in his 2012 book Islamization in Modern South Asia: Deobandi Reform and the Gujjar Response. In his acknowledgements on page 5 Singh writes:

[6] Reverend David Emmanuel Singh, a research tutor in Islamic studies at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, thanks a number of Darul Ulooms in his 2012 book Islamization in Modern South Asia: Deobandi Reform and the Gujjar Response. In his acknowledgements on page 5 Singh writes:

“I must thank… the rectors and teachers of over thirty madrasas at Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Dehradun, and Haridwar districts of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand patiently answered my questions, and many also offered their kind hospitality to me by accommodating me in their mehmankhana (guest house), especially at Saharanpur and Deoband. The public relations officer at Deoband as well as the faculty and students at Deoband spared much of their time to talk with me and reintroduced me first hand to the great Indian Islamic tradition that Deoband represents. The madrasa at Harsauli in Muzaffarnagar district has been at the very heart of the movement. The rector and the faculty there shared with me the only written source in Urdu on the early tabligh among the Gujjars—something I found invaluable, especially for the correspondences and reports of the first ‘preachers’ to their supervisors and their instructions to them.”

[7] Brannon D. Ingram, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Northwestern University, in his 2018 book Revival from Below – The Deoband Movement and Global Islam, visited and stayed at Dar al-‘Ulum Deoband in 2009 while researching his book.

Anecdotally, the manner in which graduates of Darul Ulooms in the UK, in India, and other countries, are often encouraged by their alma mater to pursue modern education, including the social sciences, in mainstream colleges and universities clearly rebut the assumption that the valuing of knowledge in Darul Ulooms does “not extend to appreciation of social scientific knowledge.” There are graduates who have gone on to study economics, geography, history, law, linguistics, politics, psychology and sociology. Clearly, if these sciences do not count, then why would these institutes (including the older first generation of pioneer scholars in the UK) encourage their graduates to study them?

Aside from the above, it may interest Gilliat-Ray to know that excerpts from the Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), the Father of Social Sciences, are included in the syllabus of many Darul Ulooms. I myself was introduced to him and his writings and theories in the third year of my studies. As a side point, as a former student at Darul Uloom Bury, I recall how the principal would often gather feedback himself or through students during and after events, clearly an exercise in social research that underscores the value of qualitative data (on one occasion I myself was handed a digital voice recorder and asked to briefly interview attendees at one of the annual Youth Tarbiyah Conferences).

Gilliat-Ray’s Second and First Consideration

Another reason that Gilliat-Ray provides for her non-access is the view that the Darul Ulooms are not interested in “outward-facing engagement.”

“The second consideration involves the nature, history, and purpose of these institutions within the Islamic tradition. Their primary objective has been the cultivation of pious and religiously-knowledgeable individuals who embody and preserve religious texts and dispositions (Lindholm 2002; Robinson 1982). The preservation of knowledge and its successful transmission from one generation to another produces an orientation that focuses upon internal teacher–student relationships, rather than more outward-facing engagement.”

What “outward-facing engagement” actually means is unclear. It could be interpreted as lack of interest in engaging with wider British society, civic society and institutes. If this is the case then this ties in with Gilliat-Ray’s first reason:

“Firstly, the origin of these religious institutions in nineteenth-century colonial India and their resistance to ‘the British’ meant that their orientation has generally been characterized as oppositional and resistant to external interference (Geaves 2015; Lewis 2002; Metcalf 1982). This stance was transferred into the British context with the migration of South Asian Muslims to the UK in the decades after World War II, and there was little attempt to engage with wider civil society, not least because of the assumption that settlement in Britain was only going to be temporary (Anwar 1979). There was neither the tradition, the expertise, the resources, nor the perceived need to engage (Joly 1988).”

This sentiment is repeated again later on in the paper:

“The individuals who pioneered the establishment of Deobandi darul uloom in Britain in the post-World War II years—especially from the 1980s onwards—were inheritors of a religious worldview that was to some extent oppositional to and suspicious of ‘the British’. Their religious training in the Indian sub-continent meant that the priority was replication of the kind of institutions they were familiar with ‘back home’…”

Much of what Gilliat-Ray writes above about the reticence of the UK Darul Ulooms to engage is based on conjecture and regurgitation. Though Gilliat-Ray writes she did not want “the institutions I was trying to access to confirm the negative ‘isolationist’ stance attributed to them in so many academic, media and think-tank accounts” this is exactly what has happened. This sentiment of non-engagement with or resistance to the British is a theme that often appears in the writings of academics and journalists who write about or ‘study’ Deobandis in the UK. As a result, I am going to spend some time deconstructing this.

The assumption that the Darul Ulooms lack interest in engaging with wider British society, civic society and institutes is simply  untrue. A cursory glance at the section above—“Darul Uloom Bury engaging the media, civic society and academics”—clearly turns this notion on its head. There is clear evidence of open days and civic ceremonies being held at the Darul Uloom, along with mayors, MPs, police and church leaders visiting the Darul Uloom. From my time at the Darul Uloom I remember representatives being sent to neighbourhood meetings and police forums. Anyone with knowledge of hadith literature would be well aware of the more than increased emphasis on respecting the rights of neighbours, regardless of faith. The personality of Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Yusuf Motala was one that was embossed with the meticulous following of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and as such he was particular in maintaining positive relations with his neighbours living in the vicinity of the Darul Uloom, often sharing gifts and flowers. (An example of Darul Uloom Bury’s interaction with a neighbour follows below in the section titled “The Deobandi approach in the UK.”)

untrue. A cursory glance at the section above—“Darul Uloom Bury engaging the media, civic society and academics”—clearly turns this notion on its head. There is clear evidence of open days and civic ceremonies being held at the Darul Uloom, along with mayors, MPs, police and church leaders visiting the Darul Uloom. From my time at the Darul Uloom I remember representatives being sent to neighbourhood meetings and police forums. Anyone with knowledge of hadith literature would be well aware of the more than increased emphasis on respecting the rights of neighbours, regardless of faith. The personality of Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Yusuf Motala was one that was embossed with the meticulous following of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and as such he was particular in maintaining positive relations with his neighbours living in the vicinity of the Darul Uloom, often sharing gifts and flowers. (An example of Darul Uloom Bury’s interaction with a neighbour follows below in the section titled “The Deobandi approach in the UK.”)

Returning to Gilliat-Ray, anyone cursorily reading her paper would assume what she has written is accurate; after all she does provide references and that also to three leading academics. References, however, can be misleading and it would, therefore, be necessary to analyse each of these references.

Prior to discussing them and since Gilliat-Ray has discussed the history of Deoband within the colonial context it would be useful to recognise that Deobandis today, as those in the past, are not homogenous. There are numerous examples from the Raj era that show Deobandi scholars and the administration at Darul Uloom Deoband interacting with the British. Yes, it was the case that, influenced by the rise of Indian nationalism from around 1920 onwards and the agitations and non-cooperation movement led by the Indian National Congress, some Deobandis participated—in their individual capacity and not on an institutional level—in the freedom movement which had a current of non-cooperation with the British Raj authorities threaded throughout it.

However, there were others within the Deobandi fraternity who remained aloof of politics. The policy of the Darul Uloom at  Deoband, for instance, was to remain apolitical. Exemplifying this were the divergent positions of the head lecturer at the Darul Uloom (Shaykh al-Hind Mawlana Mahmud al-Hasan [1851-1920]) and the then principal (Mawlana Hafiz Muhammad Ahmad, the son of Mawlana Qasim Nanautwi). While the Shaykh al-Hind was politically active in his personal capacity in opposition to the Raj, the principal was primarily concerned with the preservation and advancement of the madrasah and opposed to political activism. In fact, the principal had been conferred the title of Shams al-Ulama (Sun of the Scholars) by the British authorities. Gilliat-Ray’s comments above, however, seem to impress that the default position of the Deobandis was always oppositional to the British, that this has been transplanted into the UK following post-Second World War South Asian immigration to Britain and that this is the underlying cause of why she has been unwelcome at UK Darul Ulooms. The reality is, however, different and more nuanced.

Deoband, for instance, was to remain apolitical. Exemplifying this were the divergent positions of the head lecturer at the Darul Uloom (Shaykh al-Hind Mawlana Mahmud al-Hasan [1851-1920]) and the then principal (Mawlana Hafiz Muhammad Ahmad, the son of Mawlana Qasim Nanautwi). While the Shaykh al-Hind was politically active in his personal capacity in opposition to the Raj, the principal was primarily concerned with the preservation and advancement of the madrasah and opposed to political activism. In fact, the principal had been conferred the title of Shams al-Ulama (Sun of the Scholars) by the British authorities. Gilliat-Ray’s comments above, however, seem to impress that the default position of the Deobandis was always oppositional to the British, that this has been transplanted into the UK following post-Second World War South Asian immigration to Britain and that this is the underlying cause of why she has been unwelcome at UK Darul Ulooms. The reality is, however, different and more nuanced.

In addition to the above, in the context of India, once freedom had been secured, non-cooperation became a thing of the past and it is therefore laughable to assume that the first generation of pioneer Deobandi scholars in the UK who established the Darul Ulooms and were far too young to have participated in Independence wished to continue with Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement decades after freedom had been secured. After all, if this were the case then why did they even go to the pains of immigrating to Britain?

There is a lot more that could be said on this topic. However, it can safely be said that there are numerous incidents of Deobandi

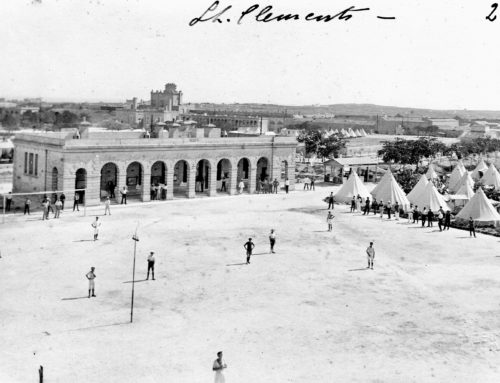

Sir James S. Meston, Lieutenant Governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh from 1912 to 1918 who visited Darul Uloom Deoband in 1915 where he delivered a speech

interactions with the British during the colonial period that clearly show that the orientation of Darul Ulooms was not one that was generally “characterized as oppositional and resistant to external interference.” The official history of the Darul Uloom at Deoband, for instance, mentions that in 1882, the first Registrar of the Punjab University, Dr Gottlieb Willhelm Leitner sent two-dozen books for the madrasah’s library. Leitner was Jewish, of Hungarian origin but a naturalised British citizen. An Orientalist, he also, incidentally, commissioned Woking’s Shah Jahan Mosque. In circa 1905 (1323AH), Sir James John Digges La Touche, Lieutenant Governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, visited the Darul Uloom, where he inspected classes, buildings, the library and spoke to students and positively commented on what the madrasah was doing. A decade later, the then Lieutenant Governor, Sir James Scourgie Meston also visited the Darul Uloom. A welcome function was held in which Meston also delivered a speech, in Urdu. The second volume of the History of the Darul Uloom Deoband includes a list of “respectable visitors” to the madrasah over the years, in which several names of senior British colonial officials are noted, including judges and magistrates.

An interesting episode that really puts on its head Gilliat-Ray’s blanket assumption is the background of a treatise on women’s right to divorce by a leading scion within the Deobandi school, Mawlana Ashraf ‘Ali Thanawi, called Al-Hila al-Najiza li al-Halilat al-‘Ajiza (The Successful Legal Strategem for Helpless Wives). Published in 1933, it holds a significant position on Muslim women’s right to divorce in India and abroad. The treatise is a fatwa that deals with the need to reform divorce laws within the Hanafi school in the new socio-political context of the British Raj. It also provides insight into how Deobandi scholars operated in a new political and social reality, an India that was no longer ruled by a Muslim power but was now colonised. In it, Mawlana Thanawi offers three solutions to the problem: seeking options in the Hanafi school, borrowing from the Maliki school or petitioning British Raj authorities to appoint Muslim judges. It is this last point that makes interesting reading for the purpose of this paper.

Living in British India, Mawlana Thanawi encouraged Muslims to petition the British government to appoint Muslim judges to oversee family law cases for a number of years; he also clarified that the judges could even be appointed by non-Muslim governmental authorities and that the only requirement was that the judges were Muslim. He sent his students to meetings held to lobby the authorities to see this materialise. Though his efforts did not bear fruit they indicate the manner in which the mawlana viewed Muslim-British relations in the new political and social reality of an India under a foreign colonial rule. The Deobandi call for petitioning the authorities at that time was a call to engage with, not isolate from, British colonial administrators.

The Deobandi approach in the UK

It was in 1981 when one of the leading Deobandi scholars of that time, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Muhammad Zakariyya Kandhalwi (1898-1982) visited the UK for the second time and stayed at Darul Uloom Bury for three weeks. During his stay at the Darul Uloom a neighbour, an English lady accompanied by her brother, visited him. The couple had tried to catch a glimpse of him on his arrival but was unable to do so as his car had already passed before her arrival. She also said she had come as she wanted the mawlana to pray for her and her brother who had cancer. The account continues that Mawlana Zakariyya “agreed whole-heartedly which prompted her to produce a gift she had brought for him, and had wrapped in decorative wrapping paper.” Mawlana Zakariyya declined the gift and said he would pray for her regardless. The lady then insisted that he accepts the gift, assuring him that it was not connected to the prayer request and that she had brought it “purely as a gesture of goodwill.” Mawlana Zakariyya then accepted the gift.

This adversarial tendency that Gilliat-Ray consistently underscores about the Deobandis in her paper is contrary to what was experienced by this local neighbour. The fact is that this lady felt very comfortable to approach the Darul Uloom to arrange this meeting. Further to this, there was no resistance to meet with a female. Such profiling of a community by Gilliat-Ray is tantamount to determining baseless assertions or providing an unacademic generic and subjective narrative.

The Deobandi worldview of living in Britain that I heard from my elders and teachers while growing up is probably most well-defined in a speech delivered by a leading Deobandi scholar, Mawlana Abul Hasan ‘Ali Nadwi, at the opening of the Tablighi Markaz in Dewsbury in 1982:

“My dear brothers, you must earn your recognition in this country. You should earn your place and leave an imprint on the host community of your value and significance. You must show your exemplary conduct is far nobler than that of other people. You must impart on them the lessons of humanity. You should demonstrate such commitment and noble virtues that impress on people that there cannot be found more upright humans elsewhere besides you. You need to establish your worth, showing what blessing and mercy you are for the country.

“If however you decide to live in an enclosed environment simply content with your prayers and fasting, apathetic to the people and society you live in, never introducing them to the high Islamic values and your own personal qualities, then beware lest any religious or sectarian violence flares up. In such a situation, you will not find safety or protection.”

The above is not isolated, but rather consolidated by other Deobandi scholars. For instance, Shaykh al-Hadith Mawlana Yusuf Motala told The Muslims News in 2011 (referenced above):

“I have been aware from my early days here that to achieve the needs of our community and success for our country we need to encourage our youth to participate in the political structure and endeavour to contribute to the civil and public spheres…

“It has also been my view that those who are politically inclined should operate within the three-party political system that exists rather than to form a new fringe political party…

“In the 1990s, while some Muslims burnt copies of the Satanic Verses, I advised that legal channels and lawyers be used against Salman Rushdie and his publisher on the grounds of blasphemous and seditious libel. Although the outcome was unsuccessful in this instance … [he would] use the same approach in a similar situation.”

The article also mentions that Darul Uloom Bury is nestled in the midst of a hundred thousand homes, of which a mere twenty are Muslim and that the mawlana suggest this could serve as an example of meaningful engagement.

“The residents do not merely tolerate the existence of the Darul Uloom but they have accepted it” adding that the “genuine engagement, generosity, warmth and the understanding of the staff, teachers and students” have contributed to this.

The article also touches on community relations and steps the mawlana himself took to calm issues and avoid divisions. The article further mentions that the mawlana continuously states that he “opposes ignorance and aspires for Muslims to serve valuable roles in society… for the one who has good intentions to provide this service, he has ample opportunities available to him…”

While Gilliat-Ray is quick to assume on the basis of limited interaction that the Darul Ulooms are not interested in “outward-facing engagement,” the above clearly show this is not the case. It would now be apt to look closely at some of the references she provides to make her argument.

Analysing references – Ron Geaves

Gilliat-Ray’s cited passage above (in her 2018 paper) references one of the writings of Ron Geaves that was published in the British Journal of Religious Education (2013), entitled “An exploration of the viability of partnership between dar al-ulum and Higher Education institutions in North West England focusing on pedagogy and relevance.” Like Sophie, Geaves also discusses why he was unable to access Deobandi Darul Ulooms. Commenting on the reticence, he says:

“Deobandi reticence to engage with outsiders has been variously analysed as due to defensive strategies of isolation developed to protect Islam in the crisis caused by the loss of Muslim power to the British in India in the second half of the nineteenth century (Geaves 1996, 152, 2007).”

On the surface, this looks like a fair comment and the fact that it has been referenced probably means it is accurate. However, there is a need to scrutinise the references, which incidentally are Geaves’ own earlier published papers: one published in 1996 and another in 2007. The second 2007 reference is, unfortunately, not included in his list of references at the end of the paper, an oversight that means we are unable to scrutinise that paper and the veracity of the comment. Geaves’ paper is not a high school essay but an academic paper put together by a seasoned academic and “authority” on Islam in Britain. Failure to list references is very unacademic and sub-standard for a seasoned academic. It seems rather an anomaly that both academics would make a similar oversight.

The 1996 reference, however, is listed and refers to a monograph that Geaves wrote entitled Sectarian Influences within Islam in Britain. Having scoured this paper, it is difficult to exactly pinpoint from where Geaves has picked his above sentiments regarding “loss of Muslim power” and “defensive strategies of isolation.” Perhaps the reference is to a passage in which Geaves writes that the Deobandi “obsession to copy the details of the Prophet’s lifestyle and appearance” was a “defence mechanism against inundation by the ways of a stronger, more powerful non-Muslim group.” If this is the case, then this particular comment has no reference and could then simply be considered to be conjecture and Geaves’ own personal opinion. In such a scenario, it would also be correct to respond by saying that Muslim scholars have focused on the Prophet’s lifestyle and appearance (in other words the hadith and fiqh) since the very inception of Islam. In fact, some of the more famous and solid works of hadith and exegesis written throughout Islamic history were written in the Islamic world well before colonialism existed. The religious sciences relating to these subjects flourished in places that would be considered Muslim lands where the question of Islam being inundated “by the ways of a stronger, more powerful non-Muslim group” did not arise.

In conclusion, it can be said that Gilliat-Ray has referenced Geaves who has referenced two of his earlier papers. One of the references does not exist and the other leads us to a paper that he previously wrote wherein the relevant section there reads more like his own personal unsubstantiated opinion void of evidence or references. It would have been prudent if Gilliat-Ray scrutinised these references prior to including them in her paper.

Analysing references – Philip Lewis

The second reference that Gilliat-Ray provides is the work of Philip Lewis, Islamic Britain: Religion, Politics and Identity among British Muslims. This assumed reticence of the UK Darul Ulooms to engage is a sentiment that Lewis repeats in several papers, including those written jointly with Yahya Birt. To begin, how should one approach Lewis’ writings and research? Fact is, Lewis has a particular fixation with the Deobandis, something that perhaps stems from his being a Church Mission[ary] Society (CMS) evangelist who spent several years in Pakistan. Throughout the British Raj and also during East India Company rule, the CMS ploughed significant resources into pre-partition India for evangelical purposes but were frustrated in their attempts at making significant inroads among Muslims due to a multiple of reasons, particularly the Deobandi madrasah network, the Tabligh Jamat and the Sufi khanqahs. There is much to be said on this topic, but it is probably useful to know that nowhere in his book does Philip mention his involvement with the CMS and missionary work, something that would probably provide readers, especially policymakers, important context and an explanation on how his writings should be approached. On the back of the book, Lewis is described as a “specialist in comparative religion. He spent six years in Pakistan and is now Advisor to the Bishop of Bradford on inter-faith issues, representing the Archbishop of Canterbury on the advisory committee of the Centre for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations in Selly Oak.” At the same time, it should be noted that despite doctrinal differences, the Darul Ulooms are not antagonistic to Christians or missionaries per se as can be seen by the amicable relations reported by Reverend David Emmanuel Singh and Murray T. Titus, as mentioned earlier in this article.

Returning to the point of discussion, Lewis’ work is something that I have read several times and at several junctures of my life. When originally published in 1994, Islamic Britain was considered ground-breaking, a study that delved into internal matters of the British Muslim community. It also set the tone and perceptions of people, including academics and policymakers, of Muslim communities and the various South Asian religious trends in Britain, including the Deobandis and the Barelwis. There are, however, numerous historical inaccuracies in his writing and unsubstantiated negative inferences that I shall save for another article.

However, for the purpose of this paper, there is only one place in Lewis’ book that may support Gilliat-Ray’s comment above that the Deobandi “resistance to ‘the British’ meant that their orientation has generally been characterized as oppositional and resistant to external interference.” On page 36 Lewis writes:

“The Deoband seminary not only re-emphasized traditional standards through the study of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, but sought to use Islamic law as a bulwark against the inroads of non-Islamic influences [29].”

This is clearly serious stuff, something that paints an us-versus-them image. Where Geaves (in his 1996 paper) failed to provide a reference to his view, Lewis on the other hand does place a reference number (the number 29) to support this statement, impressing on the reader that this text is supported with evidence. However, when the reader flicks to the book’s notes section at the back (if one can be bothered to do so), then one finds that the reference is not to a book or study, but rather a simple paragraph that gives further narrative in explaining his assumption.

Lewis writes:

“In a context where Islam is a minority tradition or feels itself threatened by other developed religions, Islamic law has always been emphasized as the decisive marker of religious identity. There are four extant schools of Islamic law within the majority Sunni tradition—Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki and Shafi’i—all named after famous scholars in early Islam. In South Asia the Hanafi school predominates.”

The above statement is indeed odd and does not provide evidence to support Lewis’ claim that Darul Uloom Deoband “sought to use Islamic law as a bulwark against the inroads of non-Islamic influences.” The four schools of fiqh have existed for centuries and have been emphasised in the corpus of Islamic literature from time immemorial, well before colonialism existed. In fact, the four schools thrived and were emphasised the most in lands and periods of time when Islamic rule was dominant.

One is also inclined to wonder why in these recent decades when debates within the Muslim world have raged on whether to follow a madhhab or not, and when opposition to the four schools ultimately leads to destructive trends such as Daesh, Lewis undermines the four madhhabs that actually act as a counterbalance to negative Daesh-like trends. It is, after all, the erudite positions found within the four schools of fiqh that are able to not only challenge groups like Daesh but also assist modern Muslims to find ways to exist as minorities in cosmopolitan modern nation states.

Anyhow, returning to what Lewis has mentioned, one is inclined to ask where this information has come from and what is the evidence to support this assumption? In the spirit of academic erudition, does Gilliat-Ray not have a responsibility to scrutinise these references prior to using them?

Analysing references – Barbara Metcalf

The third academic that Gilliat-Ray cites is Barbara D. Metcalf and her book Islamic Revival in British India – Deoband, 1860-1900 (1982). There is a marked difference in how Metcalf approaches her subject when compared to Lewis, Geaves and Gilliat-Ray. Metcalf spent a considerable time in Deoband, both at the Darul Uloom there (despite her gender) and also as a guest in the home of the principal, Qari Muhammad Tayyib Qasmi. Her understanding of Deoband is one based on extensive association and as a result, throughout her book, Metcalf shows erudition, an insider’s view and an understanding of nuances. Ultimately, she provides a holistic reading of Deoband that is at odds with the reading of other touch-and-go academics, especially on the issue of Deobandi Darul Ulooms’ “reticence to engage.”

For example, Metcalf writes that the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny of 1857 created “a scar never erased from Indo-British relations” (page 84) and continues that “once finished, the Mutiny did not constitute a major theme in the thought of the ‘ulama… the ‘ulama tended rather to eliminate the political dimension from their thought. They might take [British] government jobs as needed. But they went out of their way to avoid offense to their rulers, and they sought to avoid conflict.” (page 85)

At another place she writes, “The Deobandis, as described above, used the services of [colonial] officials in supporting their management of the school. They made sure that they conformed in every way to a posture of loyalty. [Mawlana] Rashid Ahmad [Gangohi], for this reason, refused to accept a grant of 5,000 rupees a year from the Shah of Afghanistan for fear that a political link be suspected. And the school celebrated ceremonial occasions like coronations with appropriate pomp, and observed times of crises, like Queen Victoria’s last illness, with fitting prayers and messages…” (pages 154-155)

However, the British colonial enterprise was exploitative. Metcalf writes that the ‘ulama “cherished no illusions about the basis of British rule, and attributed it solely to a desire for gain… The Deobandis had no option but to accept the worldly rulers they had, but they did not accept the rulers’ view that their motives were selfless and their culture superior.”(page 155)

In fact, “… the school from its inception was unlike earlier madrasahs. Its founders, emulating the British bureaucratic style for educational institutions, in face eschewed the informal pattern of education that the scene under the pomegranate conjures up…” (page 93) She adds that the Deobandi ‘ulama trained “‘ulama in schools modelled on a variety of British institutions whose effectiveness they had witnessed. The founders of Deoband knew such institutions well. Many of them, including three Deputy Inspectors of the Education Department, were government servants; some had attended such schools as the Delhi College; and all of them confronted with concern the influential missionary societies.” (page 94)

The above citations make clear that Gilliat-Ray’s citing of Metcalf to support her claim that the “origin of these religious institutions in nineteenth-century colonial India and their resistance to ‘the British’ meant that their orientation has generally been characterized as oppositional and resistant to external interference” is inaccurate. The image that Metcalf—the leading world academic on Deoband—paints is clearly at odds with the one that Gilliat-Ray, Lewis and Geaves conjures up. Given that only one of them has had a prolonged stay at Deoband and extensive discussions it seems safe to suggest who provides actual qualitative data that sheds a fair and balanced academic viewpoint.

Analysing references – Daniele Joly

In her 2005 paper, there is another reference that Gilliat-Ray cites to support her view that Deobandis are inherently isolationist and that is the 1987 work of Daniele Joly entitled, Making a place for Islam in British society: Muslims in Birmingham. In her paper, Joly looks at Muslims in Birmingham to illustrate the place of Islam in British society. Citing Joly, Gilliat-Ray writes:

“From among the diversity of religious ‘schools of thought’ within British Islam, the Deobandis have a reputation for ‘being the least open to British society’ (Joly, 1988: 38).

Anyone reading the above would be impressed to believe that Deobandis have a “reputation” for “being the least open to British society” and that an academic, namely Joly, supports this view. What Joly writes in her paper, however, is not exactly what Gilliat-Ray suggests. It is in a section listing “non Sufi mosques” that Joly lists the Deobandis. She writes:

“The Deobandis, who take their name after a village in India, and seem to be the least open to British society.”

When citing the above, Gilliat-Ray misses the modal verb “seems” that Joly uses as a qualifier, something that linguistically denotes a sense of uncertainty and caution, and the need to be critical about her judgement. Its usage reminds readers of the limitations of the research and to be cautious. However, when Joly is cited in Gilliat-Ray’s work the modal verb “seems” is not included and the sentence is structured in a way that gives the reader the impression that the Deobandis certainly “have a reputation for ‘being the least open to British society.’”

Aside from the above linguistic point, the fact that Joly considers Deobandis as non-Sufi (when this is clearly not the case) and the fact that her fieldwork focused just on Birmingham and not the whole of the UK, one wonders whether her suggestion can be considered representative of Deobandis on the whole. One is also led to question how credible her understanding of being “Sufi” is. Metcalf certainly does not call the Deobandis non-Sufi. The term “Sufi” in academic literature and political conversations is used to imply being passive and apolitical. A “non-Sufi” would imply the opposite.

Gilliat-Ray’s Third Consideration

Out of Gilliat-Ray’s four reasons, there now only remains one, which is as follows:

“The third factor that probably influenced our lack of access revolved around the socio-political climate at the time of the intended research. It was just a few years after 9/11, and there was new and growing suspicion in relation to the potential for terror attacks in the UK. Islamic institutions were under scrutiny in an entirely new way, and subject to increasingly intrusive investigation by the media, counter-terrorism officials, and government inspectors (Versi 2003). The last thing that staff in the darul uloom wanted was further “research”.”

This is a fair comment and may perhaps be true. Of course, Gilliat-Ray is not a journalist or from government. However, the reality is that academics on Islam in Britain have over the decades been commenting on the Deobandis in ways that are inaccurate and perhaps this may be the reason behind Gilliat-Ray’s failure to access Darul Ulooms. For instance, one of Gilliat-Ray’s colleagues, Ron Geaves, speaking to the Sunday Telegraph in 1997 said:

“Ron Geaves, Professor of Islamic Studies at Wolverhampton University, said the increase in Deobandi teachings in Britain was a cause for concern. ‘The Deobandis are obsessed with fatwas. It’s how they control their members and how they would like to control the rest of the Islamic world. Deobandis see their way as the only correct route and are political in their teachings.’”

This comment was published in a mainstream broadsheet as far back as 1997, well before the hysterical media and government focus on Islam and Muslims that we have witnessed over the last two decades. As an academic, one would expect Geaves to clarify what the exact “cause for concern” was. One is also led to question whether the focus on fatwas is exclusive to Deobandis to the exclusion of other Islamic groups and why this is so remarkable that it needs to be mentioned. Moreover, the basic fact that fatwas are answers to queries sent in by the general public, not manufactured edicts, indicates a fundamental lack of knowledge on how the institute of ifta works. It is also not very academic, especially for a sociologist, to comment on a group in a generalised fashion and to treat them as a monolith. This comment falls short of what is expected of a respected academic, leaving one wondering why Geaves indulged in such negativity.

Likewise, in the mid-noughties when there was a campaign to stop the building of a Tablighi Jamat mosque in London close to London’s 2012 Olympics site, Philip Lewis was widely cited in the press speaking about how allowing the mosque to be built could lead to a “ghetto” for terrorist sympathisers. Perhaps, Gilliat-Ray simply was denied access due to negative sentiments that are espoused by her fellow social scientists.

It could also be argued that Lewis’ modus operandi for field research has created a negative perception of social scientists within the Darul Uloom community. In her first paper, Gilliat-Ray describes how Lewis adopted “a low key strategy for entry to the field, by simply turning up at public events, and ‘hanging around.’” That coupled with his negative perceptions of Deobandis in general that is clouded with his evangelical faith background (as discussed above) probably played against Sophie. After all, Lewis also acted as “consultant” to the pilot project that she embarked on in 2005. The “hanging around” way of research seems not just to be the forte of Lewis, but also that of Geaves who also recently held a position at Gilliat-Ray’s Centre of the Study of Muslims in Britain at Cardiff University.

Another point that comes to mind is Gilliat-Ray’s sensational and sinister commentary on the word “research” in her 2005 paper in a paragraph discussing how the Darul Ulooms may have rejected her request for access due to heightened suspicions of Muslim communities following 9/11:

“Against the background of this, it is likely that my use of the very word ‘research’ became politically charged and was automatically translated as ‘investigation’ (which in the Deobandi mindset and tradition will mean almost inevitably unwelcome, negatively intentioned ‘investigation’).”

This is condescending and neither have these academics done any research on this. Rather, there is a nuanced imposition of meaning introduced for the term “research” that very subtly augments the aim of Gilliat-Ray’s paper.

Was Gilliat-Ray denied access due to her gender?

Having discussed Gilliat-Ray’s four reasons as to why she was denied access, it would be apt to consider another reason that Ron Geaves has previously mentioned regarding Gilliat-Ray’s non-access, in other words her gender:

“I was reading back through Gilliat-Ray’s very very good article that she gave me … in which she talks about her non-access to Deobandi Darul Ulooms. Now, I’m not bragging but I have accessed, and not only in India but also now in Britain. It’s a very interesting point, because when I start thinking about—and I might be wrong and Gilliat-Ray might want to have this conversation afterwards—it seems to me that what became primary in the issue of her non-access and my access was not an issue of Muslimness but an issue of gender…”[2]This was mentioned in September 2014 at the Islam-UK Centre and Muslims in Britain Research Network conference held at Cardiff University.

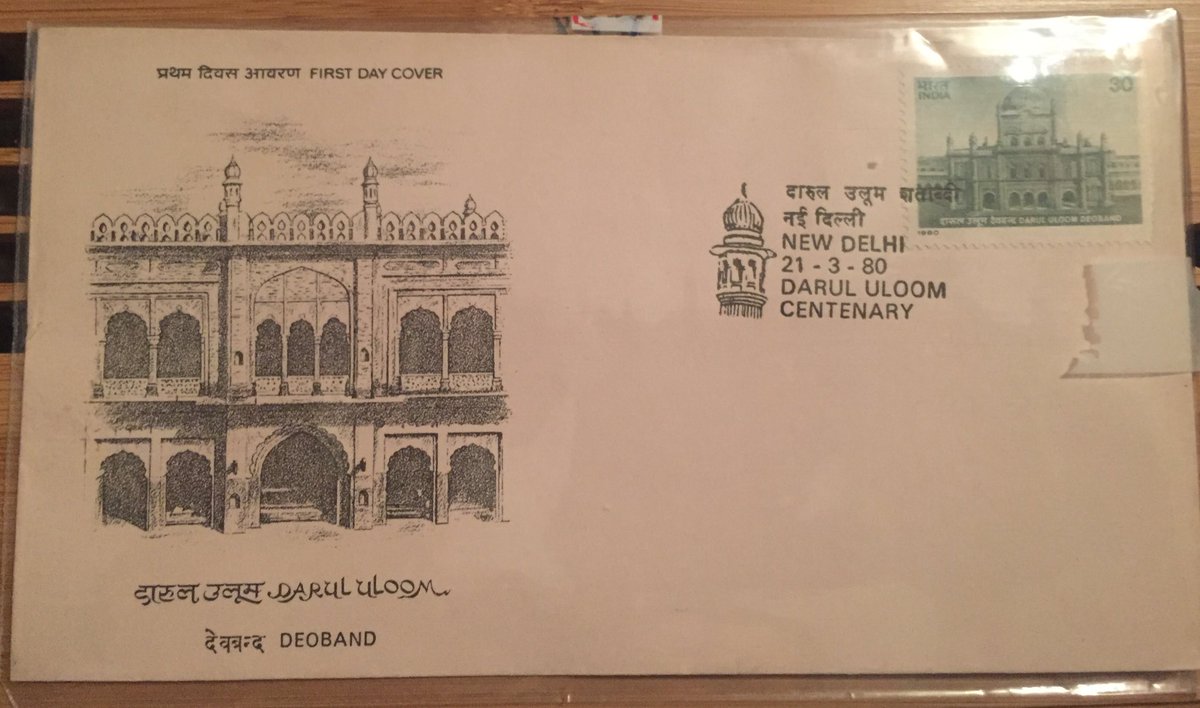

Urdu article in the Jang newspaper on Indira Gandhi’s visit to Darul Uloom Deoband in 1980

Gilliat-Ray herself, in her first paper, also confides the same that her “gender no doubt a considerable obstacle.” In response, it would be apt to say that female researchers have previously accessed Deobandi Darul Ulooms for research purposes, for example Gail Minault Graham and Barbara Metcalf as mentioned above, both of whom were hosted at Deoband by the then principal, Qari Muhammad Tayyib Qasmi. Anyone who has spent time at the Darul Uloom in Bury, for example, would know of the English teacher who was a familiar sight for decades. You can even see her in this 1980 ITV programme. Likewise, there have been many female visitors to the Darul Uloom, such as reporters, OFSTED inspectors and members of civic society as highlighted in the section entitled: “Darul Uloom Bury engaging the media, civic society and academics.” When Darul Uloom Deoband held its centenary celebration in 1980, the chief guest was the then Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi who also delivered a speech in chaste Urdu on the occasion. Dressed in her signature sari, it must have been obviously clear to the maulvis there that she was definitely female.

Informants’ lack of knowledge

There is one other reason that Gilliat-Ray mentions as to why she was perhaps denied access to the Darul Ulooms and that is something disclosed to her by an unnamed Darul Uloom graduate who purports that her non-access may have been due to the Darul Ulooms not being well maintained:

“More positively, a small number of graduates from Deobandi darul uloom who had read my article made contact, and considered my reflections on lack of access as accurate evaluations. They supplemented my explanations with ideas of their own that were far more mundane compared to my speculative rationalizations about the relative value of different kinds of knowledge. For example, I was informed that these institutions had historically not always been able to maintain generally accepted standards of hygiene and cleanliness, and that there may have been a sense of shame at allowing strangers to view premises that were not well-maintained.”

To begin, this is a self-assertion that cannot be verified. What Gilliat-Ray is saying is that according to her Darul Uloom informant she was denied access because the madrasah premises were unclean. How can it possibly be conceivable that her non-access hinged on this? If this was the case then the civic events held at Darul Ulooms (as listed earlier in this paper) would not have taken place. Likewise, Darul Ulooms are routinely inspected by OFSTED—clearly if access is dependant on cleanliness then inspections would not take place. This comment is based on conjecture and speculation. In my own experience as a former student at Darul Uloom Bury, cleaning schedules were in place and diligently followed on a daily basis, something that would be upped in preparation for external visits. It would also be apt to reproduce an excerpt on cleanliness from an OFSTED report for Darul Uloom Bury from 2005 when Gilliat-Ray’s first paper was published:

“The boarding accommodation was found to be clean, adequately decorated, heated and naturally ventilated. The furniture provides the basic essentials. Lack of funding and basic fees prevents further improvements to the environment.”

Revisiting Gilliat-Ray’s 2005 paper: the four examples of denials

In her 2005 paper, Gilliat-Ray mentions that a “number of individuals and organizations have tried to access dar ul-uloom for different purposes, most of which have been unsuccessful” and that she has “accumulated various ‘denied access’ accounts.” She then goes on to list four attempts.

[1] The first is a non-Muslim male doctoral researcher who in the 1990s “found himself an unwelcome visitor to the Dewsbury centre, and was ‘asked to leave and never come back.’”

The researcher Gilliat-Ray is referring to is most likely Geaves who mentions this episode in his paper Sectarian Influences within Islam in Britain. Geaves is someone Gilliat-Ray has extensively quoted in her paper and it is a wonder why she feels the need to not mention him here by name. Further to this, Geaves’ account is a one-sided single account and I would be interested to hear the other side of the story. His personal views on Deoband and the manner in which he has approached Deobandis in general (as discussed in this paper) perhaps played a part to his non-access.

[2] Quoting the Diocese of Bradford’s newsletter, Gilliat-Ray writes that the Bishop of Bradford’s request to a “local Imam training seminary” for some of their priests to visit was refused. Again, this is a one-sided account and I would be interested to know the perspective of the other side. It may be the case that they were refused access due to negative perceptions that people within the Darul Uloom community might have developed regarding Philip Lewis who has previously advised Anglican Bishops in Bradford on Christian Muslim relations. There may be other reasons, but this is one that is plausible.

[3] The third incident is the refusal to give access to a Channel 4 team who were trying to make a documentary programme regarding preachers from a range of faith backgrounds. Gilliat-Ray mentions that “they had exhausted virtually every possible avenue of access. Clearly, a television camera would be intrusive to the life of these enclosed communities, and the lack of access unsurprising.”

To begin, Gilliat-Ray may not be aware, but communications teams in organisations from within the public and private sectors often receive requests of this nature from documentary makers. Organisations are at liberty to accept and refuse permission, a decision that they make depending on their individual circumstances. Public bodies often refuse permission and for a Darul Uloom to do so is in no way any different to how a hospital, university, college, school, nursery or council refuses permission. Why is refusal to film in a Darul Uloom treated differently to how permission is refused in a hospital or educational institute? However, what we do know, as discussed earlier in this paper, is that Darul Uloom Bury has previously allowed its students, staff and premises to be filmed and featured in two documentaries on two separate occasions. Both were for Credo, a religious affairs programme produced by London Weekend Television for ITV and broadcast on Sunday evenings, in 1980 and again in 1985. This clearly tells us that, contrary to what Gilliat-Ray says, a television camera was not “intrusive” and that these communities are not “enclosed.”

[4] The fourth incident relates to an unnamed Muslim scholar who asked an unnamed Darul Uloom for a copy of their curriculum for his personal research and was denied permission for this. I would be interested in the circumstances around this denial. However, the curricula of several Darul Ulooms from the UK and abroad are quite readily and effortlessly available online. It is not the case that the syllabi of Darul Ulooms are enshrouded in some sort of mysterious unknown. OFSTED inspectors not only have access to the syllabi of Darul Ulooms that they inspect but also scrutinize them. In fact, the curriculum of Darul Uloom Bury is included in Islam in Preston (1980). Philip Lewis’s Islamic Britain (1993) also goes into much detail regarding the curricula of UK Darul Ulooms. Likewise, Geaves includes the curriculum of Darul Uloom Deoband in Sectarian Influences within Islam in Britain (1996) along with a detailed discussion on the differences between it and the curricula of two UK Darul Ulooms. In light of this, one is led to ask what it is that Gilliat-Ray is trying to insinuate by mentioning this supposed denial?

Conclusion: when history is based on errors

For me, much of the assumptions and views about Deobandis in general by academics in the UK are at times inaccurate and there is a history of this as demonstrated above. It is interesting to see how Gilliat-Ray bases her one experience with Darul Ulooms post 9-11 to stereotype an entire community. In this article, I have taken a set of data regarding Darul Ulooms that show that they are, contrary to what she writes, outward looking. Non-access is not the default Deobandi position and perhaps Gilliat-Ray’s non-access boiled down to an element of trust (especially in light of comments and the insinuations made by other academics as shown above). While, academics writing about Deoband such as Metcalf and Ingram on the other side of the Atlantic offer a more accurate and balanced picture, the academic scholarship looking at Deobandis in Britain has been quite shoddy.

The blowback, however, is how these papers based on flimsy assumptions negatively affect Muslim communities in the UK and perpetuate a lack of trust. There is evidence of journalists taking the writings of academics on Deoband and weaving narratives that are simply untrue and inaccurate. I recently came across an intriguing article in the New York Times[3]https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/22/world/asia/the-jungle-prince-of-delhi.html that has nothing to do with this paper but provides food for thought when it comes to UK academics studying Deoband. The journalist writes:

“Among the family papers was a column from The Statesman, published in 1993, with the headline ‘When History Is Based on Errors.’ Two paragraphs had been marked.

“‘Have you noticed that a factual error appearing in respected printed form tends to be copied by other researchers in the same field, until, inevitably, it competes with the truth for credibility?’ it read. ‘The writers who perpetuate these mistakes rarely do so from evil motive: They have no axe to grind, they simply do not have time to check and double-check each fact, so they rely on the scholarship of their predecessors.’”

As a journalist, I’ve seen this happen lots of times and having worked as a newspaper sub-editor, and that also in the Middle East, I know how inaccuracies can take a life of their own. That is why the media should be taken with a pinch of salt. Academics, on the other hand, are supposedly subject to scrutiny and rigour, something that in the study of Deobandis in the UK has not taken place. When it is the case that policymakers and governments take the writings of these academic khutputs seriously, then the impact on minority communities is huge. The “notoriety” and negativity that Gilliat-Ray’s first paper gained was definitely not based on “rumours” and “gossip” but actual readings of her writings.

“O you who believe, if a sinful person brings you a report, verify its correctness, lest you should harm a people out of ignorance, and then become remorseful on what you did.” (Surah al-Hujarat: 6)

Views expressed by our writers are their own and do not necessarily reflect Basair.net’s stance.

References

| 1 | According to Hobson Jobson (the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words and terms from Indian languages), the word khutput “is a native slang term in Western India for a prevalent system of intrigue and corruption” and that the general meaning of khutpuṭ in Hindustani and Marathi is “wrangling” and “worry.” It is in this sense that this word has been used in this article. |

|---|---|

| 2 | This was mentioned in September 2014 at the Islam-UK Centre and Muslims in Britain Research Network conference held at Cardiff University. |

| 3 | https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/22/world/asia/the-jungle-prince-of-delhi.html |

Leave A Comment