By Mufti Zameelur Rahman

Dr Asim Yusuf, author of Shedding Light on the Dawn, recently delivered a talk at Ebrahim College on the “Anatomy of a Fatwa,” in which he made several startling claims. His talk was apparently aimed at showing that we are in a “post-madhhab age” and fiqh has to be conducted differently to how it was in the past. In doing so, he makes a number of problematic claims, most of which were unsubstantiated or vague. It is not the purpose of this piece to address all such problematic claims. For a basic understanding of why classical madhhab-based jurisprudence is necessary, one can read the links provided in the footnote.[1]

Below we will address Dr Asim’s claims about the principle of istiḥsān in the Ḥanafī school. He attempts to show that istiḥsān amounts to an individual using their own ethical judgement, divorced of a legal argument, to come to some conclusion on Islāmic law. This is a mistaken, and obviously highly problematic, understanding of the Ḥanafī principle of istiḥsān, and is in fact a mischaracterisation of it refuted by early Ḥanafī jurists.

As will be demonstrated below, istiḥsān, as adopted by the Ḥanafī jurists, is simply a legal evidence or argument that clashes with an apparent analogy (qiyās). On the rare occasion, qiyās would be favoured over istiḥsān, while, on the most part, jurists have given preference to istiḥsān.[2] Thus, istiḥsān is not a personal judgement based on one’s subjective ethical preference, but is a substantive legal argument (dalīl) that often preponderates over qiyās.[3]

Dr Asim Yusuf’s Comments on Istiḥsān

The following is a transcript of Dr Asim’s comments about istiḥsān:

“Then there is istiḥsān, and istiḥsān is another theory that dare not speak its name…Istiḥsān is the default of the early Ḥanafī madhhab. The early Ḥanafī school leaves qiyās for istiḥsān on many, many, many occasions. Mālik said istiḥsān is nine-tenths of the law. Shāfi‘ī said ‘man istaḥsana faqad sharra‘a’ – the one who does istiḥsān is inventing their own Sharī‘ah…What’s istiḥsān? It’s you put the scripture and the situation into one end of the machine, that’s the qiyās machine, it comes out of the qiyās machine, and you kind of go, ‘What?! Nah,’ and you say, ‘Forget that, I’m doing this instead.’ That’s what istiḥsān is – on the basis of a deep understanding of the law…I’ve got the equation, the equation gives me this answer, but this isn’t a good answer, so what I’m going to do is rather than use Newtonian physics I’m going to use relativity. And relativity, which is much more complicated, gives me the right answer. How does the jurist determine what’s the right answer? Istiḥsān means what seems good to the jurist. How does the jurist judge what is good? What is the standard? What does it say about the philosophy of the law? What does it say about ethics and so forth?…

“There is one more question about istiḥsān: Where on earth is it in the Uṣūl books? In the Ḥanafī Uṣūl books, where’s the chapter on istiḥsān? It’s absent, it’s vanished, it was never there, and yet it’s one of the foundational principles of the Ḥanafī madhhab. Where’s it gone? Why isn’t it there? Great discussion for another time.”

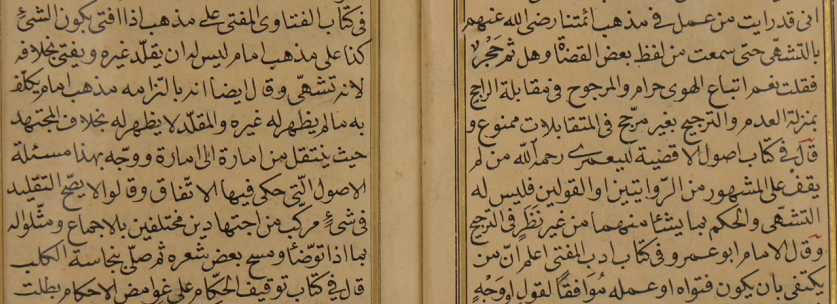

Chapters on Istiḥsān in Ḥanafī Books on Uṣūl

To address Dr Asim’s last point first, he displays an incredible degree of ignorance, and an incredible amount of confidence in his ignorance, in claiming that Ḥanafī books on Uṣūl do not have chapters on istiḥsān. The well-known early works on Ḥanafī Uṣūl al-Fiqh by Abū Bakr al-Jaṣṣāṣ (305 – 370 H), Abū Zayd al-Dabūsī (367 – 430 H), Fakhr al-Islām al-Bazdawī (ca. 400 – 482 H) and Shams al-A’immah al-Sarakhsī (d. ca. 490 H) all have chapters on istiḥsān.[4]

Istiḥsān in the Ḥanafī School

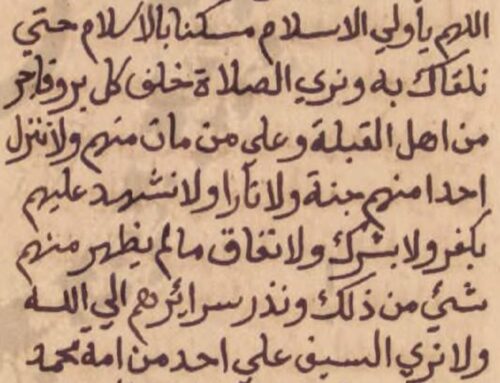

All of these Ḥanafī scholars explain that istiḥsān does not mean, or amount to, a jurist using his own judgement to come to a legal ruling, and is in fact a transparent legal (shar‘ī) argument (dalīl). Al-Dabūsī says: “Based on this [linguistic meaning of istiḥsān] some jurists have assumed that one who advocates istiḥsān has abandoned qiyās and legal proof (ḥujjah shar‘iyyah) using his own assessment of what is good – abandoning it without any legal proof. Based on this, they have attacked our ‘Ulamā’.”[5] Hence, this mischaracterisation of istiḥsān, based on which some non-Ḥanafīs attacked the Ḥanafīs, is according to Dr Asim precisely what istiḥsān means!

Al-Sarakhsī and al-Jaṣṣāṣ state that there are two types of istiḥsān. The first is where the Sharī‘ah has left something to the judgement of an accountable individual. For example, the Sharī‘ah says the father must feed and clothe the mother of his nursing child according to common equitable standards (Qur’ān, 2:233); this standard will of course be determined by an individual based on his good sense.[6] No jurist would disagree with this meaning of istiḥsān.[7]

The second type, which is what a mujtahid jurist uses for the derivation of law, is defined succinctly by Imām al-Sarakhsī as follows: “It is an evidence that contradicts an apparent qiyās that comes immediately to the mind before thinking carefully about it; but after thinking carefully about the ruling of the situation and similar [situations] from the principles, it becomes clear that an evidence that contradicts it is superior to [the apparent qiyās] in strength, so acting on it is necessary. They called this ‘istiḥsān’ to differentiate this type of evidence from the apparent evidence that came immediately to the mind before thinking deeply.”[8]

Hence, istiḥsān is not moving away from evidence altogether, but is favouring an evidence that overrides another evidence, namely, a superficial or apparent analogy. According to al-Sarakhsī, this amounts to “giving preference to acting on the stronger of two evidences.”[9] Since the legal argument (dalīl) that overrides analogy is not a single, fixed, type of evidence, Ḥanafī jurists collectively refer to all such types of arguments as “istiḥsān”.

Al-Jaṣṣāṣ, al-Dabūsī and al-Sarakhsī all point to several types of evidence used in the process of istiḥsān. One type of evidence is, in fact, scriptural texts (nuṣūṣ)! In other words, istiḥsān – the overriding of an apparent qiyās – can be based on an explicit scriptural text. An example is a fasting person who eats or drinks because of forgetting that they were fasting. Based on qiyās (analogy) with ṣalāh, one would assume that the fast breaks and will have to be repeated. However, this qiyās is superseded by an explicit ḥadīth in which the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allāh be upon him) said the person’s fast is valid. Thus, here the istiḥsān is in fact based on a scriptural text.[10]

In many books of Ḥanafī jurisprudence one will find the phrase “the basis of the istiḥsān is…” (wajh al-istiḥsān), followed by an explanation of the underlying legal basis for leaving an apparent qiyās on a given issue. When the founding Ḥanafī imāms used the principle of istiḥsān, they would sometimes point out the basis (wajh) of the istiḥsān. If istiḥsān was merely a jurist’s personal preference, this evidence-based approach to istiḥsān would not make sense.

For example, Imām Muḥammad (132 – 189 H) discusses the ruling of a person who, when praying a four rak‘āt optional (nafl) ṣalāh, forgets to sit down in the second rak‘ah. Based on strict analogy, his ṣalāh should be invalid because in an optional ṣalāh, each set of two rak‘ats is effectively an independent ṣalāh, and hence the sitting in the second rak‘ah is the “final sitting” of the first set of two rak‘ats – and if the final sitting is omitted, the ṣalāh is not valid. However, Imām Muḥammad explains that here qiyās is abandoned in favour of istiḥsān. The basis of istiḥsān here is an analogy with obligatory prayers, in which missing out the sitting after two rak‘ats in a four-rak‘āt ṣalāh would not invalidate the ṣalāh but would only necessitate sajdat al-sahw.[11]

Another example is on the ruling of a small quantity of water from which a predatory bird drinks. Based on an analogy with predatory mammals, one would assume the water becomes impure and cannot be used for wuḍū’. Imām Muḥammad however explains that the ruling is not the same, and the leftover water of a predatory bird can be used for purification though with some reprehensibility.[12] Al-Sarakhsī explains that this is based on a process of istiḥsān. While according to an apparent analogy with predatory mammals, one would assume the leftover water of predatory birds is impure, there is an important difference between them. Predatory mammals drink with their mouths resulting in contamination with their saliva but predatory birds drink with their beaks which does not result in contamination; and since the impurity of the water is based on contamination with impure saliva, the ruling of the leftover water of predatory birds will not be the same as that of predatory mammals.[13]

These are just a few examples from the early Ḥanafī school which demonstrate clearly that istiḥsān was a process of legal reasoning that was based on arguments and proofs, and was not merely a jurist’s personal preference.

Istiḥsān in the Mālikī School

Imām al-Shāṭibī (d. 790 H), the great Mālikī jurist and legal theorist, has a lengthy discussion on istiḥsān in his famous work on bid‘ah, al-I‘tiṣām.[14] He explains why istiḥsān as adopted by the jurists of the Ḥanafī and Mālikī schools does not amount to a jurist arriving at a legal opinion using his own judgement or based on some ineffable personal feeling or intuition.

Quoting Qāḍī Abū Bakr ibn al-‘Arabī, al-Shāṭibī explains that istiḥsān boils down to giving one evidence priority over another[15]; for example, an apparently general ruling is qualified or specified in some cases based on some other evidence.[16] Al-Shāṭibī explains that although Imām al-Shāfi‘ī spoke against istiḥsān, he would not argue against the meaning which the Ḥanafīs and Mālikīs give to it. He says: “Since this is the meaning of istiḥsān according to Mālik and Abū Ḥanīfah, it does not go beyond the evidences at all, because some evidences qualify others and some specify others, like the evidences of the Sunnah with those of the Qur’ān. Al-Shafi‘ī would not reject something like this at all.”[17]

To demonstrate his main point that istiḥsān “does not go beyond the evidences”, al-Shāṭibī lists several examples of istiḥsān from the Ḥanafī and Mālikī schools. One example he mentions relates to oaths (aymān). When a person swears by Allāh on something, and then the oath is broken, he or she will have to atone for the broken oath. Hence, the wording of an oath is important in determining whether an oath is broken. Words can have a linguistic/dictionary meaning but also a conventional meaning. Al-Shāṭibī explains that the conventional meaning is given preference in oaths over the linguistic meaning, and this is an example of istiḥsān, as one type of evidence – the linguistic meaning – is superseded by another type – the conventional meaning.[18]

Al-Shāṭibī quotes Imām Mālik saying istiḥsān is nine-tenths of knowledge and at times overpowers qiyās. He then explains that we cannot take istiḥsān to mean “what [the jurist] assesses to be good based on his intellect, or an evidence that makes an impression on the mind of the mujtahid which is difficult to express,” as this is certainly not nine-tenths of knowledge and nor does it overpower qiyās![19] In fact, al-Shāṭibī explains that such an understanding of istiḥsān opens the door to innovation and heresy.

Concluding Remarks

The imāms and jurists of the early period were primarily seekers of truth who argued based on an objective assessment of the evidence. It is precisely this reality that makes them worthy of being followed and distinguishes them from many of those in later times, especially in this era of upheaval, revisionism, postmodernism and deconstructionism. The view that the early jurists were acting on personal preference and that this was the “default” methodology they employed on many rulings would, therefore, be a striking inversion of reality. In fact, it is tantamount to insinuating that a major portion of the madhhab was manufactured on nothing more than the jurists’ disgruntlement with what came out of the “qiyās machine”, a term which in itself exemplifies how the juristic expertise of the fuqahā’ is seriously underplayed.

[1] https://theislamiclens.wordpress.com/2017/07/25/understanding-modernism-thoughts-on-muhammad-nizamis-essay-misunderstanding-traditionalism/

http://ahlussunnah.boards.net/thread/380/anaf-muft-today-transmitters-capable

http://ahlussunnah.boards.net/thread/374/al-sh-ib-on-madhhab

http://ahlussunnah.boards.net/thread/379/brief-explanation-on-necessity-madhab

[2] Taqwīm al-Adillah, Maktabat al-Rushd, 3:406

[3] ibid. 3:406-7

[4] al-Fuṣūl fi l-Uṣūl, Wizārat al-Awqāf, 4:221-253; Taqwīm al-Adillah, Maktabat al-Rushd, 3:403-11; Uṣūl al-Bazdawī, Dār al-Bashā’ir al-Islāmiyyah, p. 611-14; Uṣūl al-Sarakhsī, Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyyah, 2:199-208,

[5] Taqwīm al-Adillah, 3:403

[6] Uṣūl al-Sarakhsī, 2:200

[7] ibid.

[8] ibid.

[9] Uṣūl al-Sarakhsī, 2:201

[10] Al-Fuṣūl fi l-Uṣūl, 4:246; Taqwīm al-Adillah, 3:408; Uṣūl al-Sarakhsī, 2:202

[11] Al-Aṣl, 1:160-1

[12] Al-Aṣl, 1:25

[13] Uṣūl al-Sarakhsī, 2:204

[14] Al-I‘tiṣām, Maktabat al-Tawḥīd, 3:59-107

[15] Al-I‘tiṣām, 3:63

[16] ibid.

[17] Al-I‘tiṣām, 3:65-66

[18] Al-I‘tiṣām, 3:68

[19] Al-I‘tiṣām, 3:64-5

Interesting. Here is an informative article which rounds up ‘istihsan’ in a brief manner :

http://www.myislaam.com/fiqh/istihsan/

I dont know how people make such outlandish claims about concepts like istihsan and think nobody will notice. Worse still is that people are willing to accept such ideas because they know no better. Articles like this one are good to help people differentiate what’s right from what’s wrong.

Have you watched his video? He comes across as someone with a serious superiority complex. I wouldn’t hold my breath for any kind of clarification or response.

Some of the widely-studied texts on Ḥanafī Uṣūl al-Fiqh also have sections on istiḥsān, like al-Manār/Nūr al-Anwār, al-Tawḍīḥ/al-Talwīḥ and al-Ḥusāmī.

Were al-Manar etc. written in the pre-modern period? Looking at his full statement, it seems that Dr. Asim meant to say that Istihsan was part of the early Hanafi Usul but vanished in the latter. I can see why this might be true for example in Usul Ash-Shashi, Ihstihsan is absent. In which contemporary books of Hanafi Usul Al Fiqh taught in the Darse Nizami is there a chapter on Istihsan?

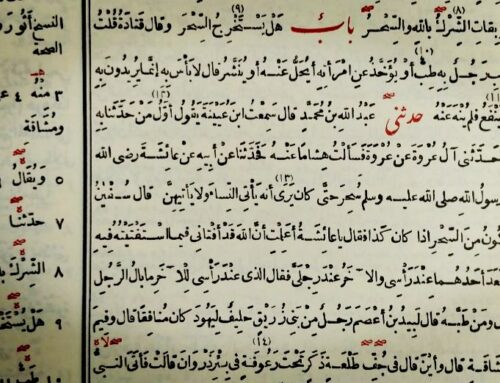

Here is a contemporary work which is part of the syllabus in many parts of the World.

الموجز في أصول الفقه

للفقيه الشيخ عبيد الله الأسدي

A detailed chapter on Istihsaan from Pg. 257-263

Is Usul Shashi a latter or earlier book? Contradictions in your statement.

Thank you for the correction. Even if Dr. Asim is wrong, his approach has significant appeal among many who are grappling with modernity. He has enough grounding in traditional Islam that makes him a scholar worthy of following. I was in his company recently in a gathering of Dhikr and I felt like I was in Jannah. A sincere student of a Wali, the fruits of his works speak for themselves. I hope and pray you also taste the same sweetness from the Ulema you follow.

Having studied under traditional ulama doesn’t give you a license to make loads of unfounded claims which go against the tradition. That doesn’t even make sense.

In that video Asim Yusuf makes a whole bunch of wild, unjustified and unsubstantiated claims with absolutely no evidence or references to back them up whatsoever. It’s the same thing Akram Nadwi does all the time. Ebrahim College seems to have a thing for people like this.